"Montauk to Manhattan: An American Novel'" by Thomas Maier - Part 3

'Montauk to Manhattan: An American Novel' by Thomas Maier - Part 3

Editor’s note: This is the third of a three-part series in which Dan’s Paperspublishes excerpts of Thomas Maier’s new book Montauk to Manhattan: An American Novel, published on July 9 by Post Hill Press.

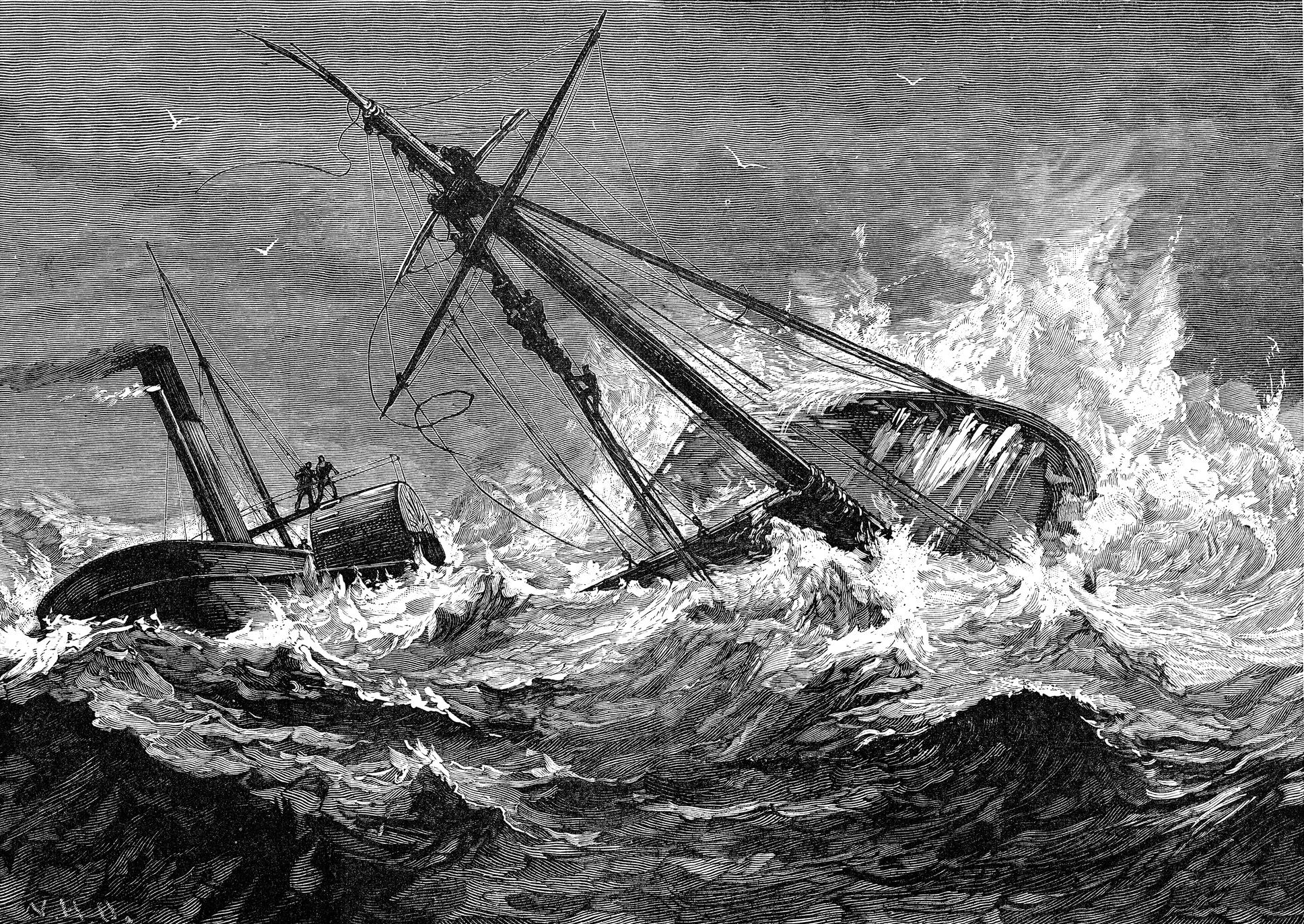

Montauk to Manhattan: An American Novel Chapter 3: The Shipwreck Scene

Shooting a Hollywood production, particularly at a remote location along the Atlantic Ocean, was fascinating to my untrained eyes. During the interminable wait that morning, I pulled out my iPhone to take a few photos, planning to show them later to friends. Maybe even post a few snapshots on social media to help promote the book’s lagging sales.

“Excuse me, are you taking my picture?”

Max Kirkland’s associate executive producer, Penelope “Penny” MacPharland, an intense, wiry woman seated in another director’s chair, got up and stood facing me, as if to block the field of vision of the iPhone’s lens.

“I can’t have you taking my photograph,” MacPharland insisted. “Are you going to post my photo online?”

She didn’t wait for my answer. “I once got in trouble because someone saw my photo on Facebook when I was supposed to be somewhere else. Please assure me that you weren’t taking my photo. Please don’t…”

MacPharland’s request seemed to carry an unspoken threat. I quickly put away the iPhone. MacPharland could be mercurial, at least by reputation. Any scuffle with MacPharland would be undoubtedly a losing proposition.

I looked to Kirkland for relief, but he was busy speaking with others.

“Penny, don’t worry — I would never take your photograph,” I said in a lowered voice, the kind of soothing tone a therapist might use. Or a police psychiatrist might employ in talking down a deranged sniper off a rooftop. I made sure no one else heard this bizarre exchange.

For a moment, Penny kept staring at me intently, as if she could see through me, to determine if my pledge was a lie. She walked back to her director’s chair, visibly perturbed. She kept eyeing me suspiciously but said nothing more. I assumed she wouldn’t give me any more trouble.

When Kirkland turned his head, I sprung up and left my chair, the one marked “Consulting Producer” on the back. I headed for a coffee at the small craft services pavilion, an impromptu cafeteria run by workers known as “crafties” on the beach parking lot.

The studio’s money was evident all around. The encampment on this Hamptons beach, if not as sprawling as Normandy’s D-Day invasion, certainly appeared as if the circus had come to town. In a large enclosure, the craft services food servers fed dozens throughout the day, a hungry army enlisted to the cause. Seated at these dining tables were countless key grips, prop makers, on-set dressers, painters, carpenters, stunt doubles, camerapeople, stand-ins, and extras without speaking parts.

Elsewhere along the beach parking lot, mammoth moving vans, stuffed with wires and equipment, had technicians jumping in and out of them. Dressing rooms and makeup rooms, illuminated with bright lights and mirrors, were housed in air-conditioned tents.

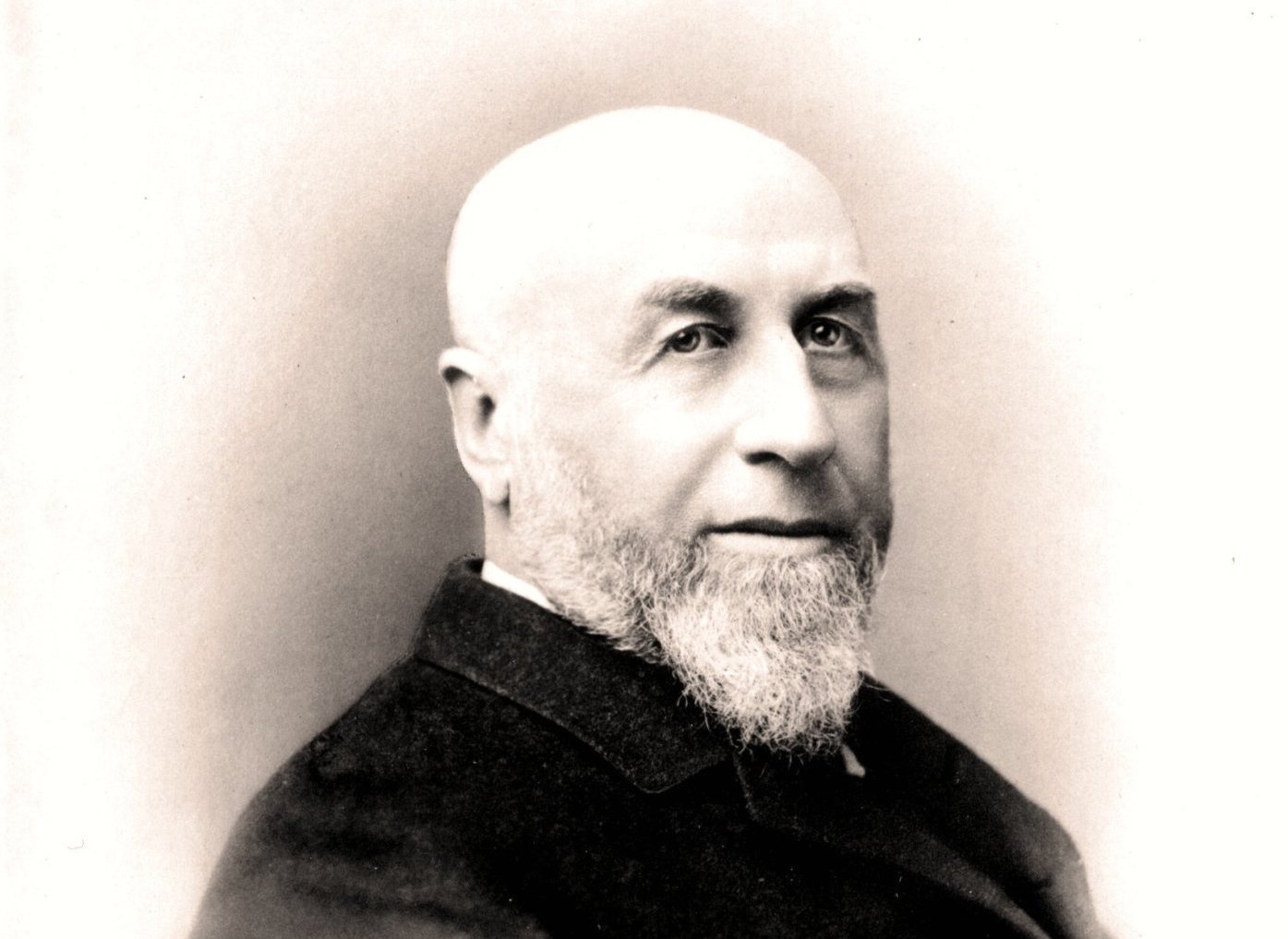

Discreetly to the side, security guards stood watch on two large motorhomes that seemed permanently affixed to the asphalt. Penny explained these “humongous” Winnebagos were fringe benefits mandated in the contracts of two top stars, Manchester and the Shakespearean actor Lester Wolf, who played the imposing character Austin Corbin (chosen because of his popularity as Commander Smith in a blockbuster space-fantasy movie.)

As I stirred my coffee at the craft services pavilion, one of the production’s lesser-known actors, a red-headed woman also in costume, approached me.

“You’re the author, Jack Denton, right?” asked Vanessa Adams, as I later learned her name. “I saw you talking to Max and figured it was you. I loved your book. Especially the part I’m playing.”

What an amusing lie. It was clear she hadn’t read a word. Her part wasn’t in my novel and had been created by Kirkland only for this pilot script. But Vanessa did exude a certain forward charm. She said everyone mistook her for a well-known star who won the Oscar for a recent musical about Los Angeles. Undeterred, she quickly got to the point of her mission.

“So, what happens to my character down the road?” she asked with the speed of a pickpocket.

Vanessa’s brashness was refreshing. It reminded me of another actor who asked this same question after an early table reading when the cast rehearsed the script. He, too, wanted to know his fate.

“You’re killed in an early episode,” I replied to him, effectively saying he’d been written out of the show. A silent shock registered on his face until he realized I was kidding. With this eager young woman, however, I didn’t have the heart to try the same joke.

“I’m helping Max with the scripts,” I explained to Vanessa, “but he decides on everything — including what happens to you.”

Suddenly, Kirkland himself appeared at the food pavilion. He was obviously perturbed by this young actress being out of place. MacPharland, standing by Kirkland’s side, mirrored her boss’s indignation.

“Shouldn’t you be out on the set getting into position, Vanessa?” Max said firmly, holding back his anger.

There was a sense of possessiveness about Kirkland as he grasped this bit player’s arm and steered her away from me. I was surprised he knew her name. Max looked at me with a scowl — like a jealous lover or perhaps simply a shepherd who had lost a sheep. Then he walked back to his director’s chair. I followed along with my cup of coffee.

After a litany of delays, the shipwreck scene finally began around noontime. Like some cinematic maestro, Max Kirkland had orchestrated an elaborate make-believe disaster. He wanted this grand ruse to appear as close to reality as possible on screen.

First, like some divine force, Max altered the weather. Though this day was mild and overcast, Kirkland arranged for a giant set of motorized fans to simulate the gale-force winds of an actual storm. Gusts of saltwater sprayed everyone’s skin and clothes.

Next, he arranged the phony shipwreck itself. Out of view of the cameras, a team of former Navy SEALs in the ocean — hired mostly for insurance reasons — released the anchor of the SS Louisiana. They let the ship drift forward slightly, until it became stuck on a fabricated sandbar, an underwater monstrosity made with dirt bags by the prop department.

Once trapped on this underwater ridge, the SS Louisiana couldn’t move. Everyone aboard was presumed a goner. Crushed by the swirling high waves, the vessel sank slowly into the ocean deep.

Screams from this ghost ship could be heard ashore. Cinematic closeups on deck of actors Lester Wolf and Kiara Manchester captured this sense of panic. Television monitors next to Kirkland picked up heartfelt cries from the cast, enough to suspend disbelief by even the most hardened theatergoer.

On the beach, the middle-aged actress, Helen Thorpe, who played Corbin’s long-suffering wife Margaret, jumped up and down in panic. According to the script, her character knew that her husband was due to land in New York that day. She sensed he might be on that ailing ship. She screamed for the team of lifesavers to rescue him.

Surrounding Corbin’s wife were a scattering of other townspeople, all portrayed by extras and uncredited actors in nineteenth-century costumes, including Vanessa. She curled her red hair up in an elaborate bun bound to be noticed. A dozen more actors, playing rescuers from the Hamptons Life-Saving Station, rushed to the scene.

“Hurry, please hurry, the ship is about to break apart!” Corbin’s wife moaned, just as the script demanded.

In this sequence, with plenty of action and little dialogue, the life-saving volunteers immediately embarked on their tasks. Husky men waded midway into the water with floating devices, but the shipwreck was too far away to reach it. Others jumped into rowboats meant to carry a few passengers. They hurdled over the waves towards the ship.

An elemental struggle raged between these men and nature. But the most difficult part of this life-saving ritual by the team involved a black cast-iron carronade, which they readied to fire into the air. In the 1800s, the purpose of this short cannon was to shoot a rope-like projectile far enough across the shipwreck’s bow so it could be tied to the ship’s tall mast. The rope line, connected to the shore, created a last-ditch method of escape for the passengers who otherwise faced certain drowning in the wild surf.

Throughout the nineteenth century, many were killed when their ship ran aground on the last leg of their journey from the Old World to the new. During one winter’s snowstorm, the crew of a schooner stuck in a sandbar tied themselves to the rigging to avoid being washed overboard — only to freeze to death before they could be saved. On her way home from Europe in 1850, author Margaret Fuller, perhaps the bestknown American woman of her era, drowned in a shipwreck less than a hundred yards from the Long Island shore. Eventually, the lost lives at sea prompted enough public outcry that the government created a string of “Life-Saving Stations” along the coast.

By the 1880s, these life-saving crew members, wrapped in cork vests, were a godsend to otherwise-doomed mariners. Everything about them and their rescue procedure appeared courageous. Once fired from the cannon, a set of ropes was tautly stretched across the murky abyss — literally a “life line” between the shore and shipwreck. Large pulleys with a leg harness, known as a “breeches buoy,” carried passengers to safety. Women were usually escorted along these ropes by limber young men called Lifesavers, who put themselves willingly at risk to rescue others.

On the set, in his tall director’s chair, Max reacted with excitement as the makeshift cannon, known as a Lyle Gun, fired away. Its concussive blast was felt by everyone.

“Did you all see that explosion?” Kirkland erupted with glee to his inner circle. “Isn’t that fantastic?!”

Max loved cinematic grandeur. Like some modern-day Francis Scott Key, he rhapsodized about the bursting red glare and the rope streaming in midair. His computer-generated shipwreck plans had been well-rehearsed with the studio’s technicians and pyrotechnic experts. The Lyle Gun performed brilliantly, he told me.

“Just don’t ask how much these fireworks cost,” he exulted, with the confident glow of a man in the winner’s circle. “Thank God, they worked.”

This opening television scene was reminiscent of the memorable 1884 oil painting by Winslow Homer called “The Life Line,” which portrayed an unconscious woman hanging over the waves and clutched in the arms of her rescuer. Homer’s masterpiece graced the cover of my book. It also emboldened Kirkland to recreate a similar opening scene of awful peril and subtle eroticism for his new television project.

With the film crew capturing each movement, the actors’ dialogue could be heard on Kirkland’s television monitors. In this scene, the characters Austin Corbin and Elizabeth Gardiner were among the last passengers remaining on the sinking ship. Some characters had jumped already into rowboats, which collapsed from sheer weight. Others tried to swim for shore, only to be swept away by the sea and drowned in dramatic reenactment.

Despite their distress, Corbin and his beautiful mistress waited their turn, as if expecting a horse and carriage to whisk them away. The well-dressed couple, lashed by the winds and rain, were soaked in brine and seaweed.

From across the ropes, a muscular young man with long, shiny black hair climbed over the boat’s railing and onto the ship’s creaking wooden deck to rescue the couple.

“You must go now — without a moment’s delay,” insisted this completely drenched Lifesaver known as Stephen Pharaoh.

Corbin immediately objected.

“My God, you’re an … Indian,” he told this Lifesaver. “I’ll have none of this. How did you become part of the Life-Saving team?”

As the winds swirled violently around them, Elizabeth Gardiner pleaded with Corbin to let her leave the ship immediately. But he refused, demanding an answer. Even in this maelstrom, Corbin wouldn’t allow himself to be indebted to a member of the Montauketts, the tribe whose lands he coveted to build his railway to Manhattan. With so little time left before the SS Louisiana collapsed, Corbin’s bigotry threatened to sink them all.

According to the script, the character of Stephen Pharaoh was central to The Life Line plot. Aware of modern-day sensibilities, Kirkland had cast the handsome up-and-coming actor Johnny Youngblood — said to be a Native American originally from Oklahoma — in the role as Pharaoh, rather than some white actor.

Youngblood had been a rock star before discovering acting. With his good looks and charisma, Youngblood resembled Johnny Depp or a young Marlon Brando. He seemed a natural for the pivotal role of Stephen Pharaoh, a sympathetic character that Kirkland knew audiences, especially women, would respond to. As Pharaoh, Youngblood vowed to rely on stunt doubles as little as possible — an idea Max encouraged — and convinced other actors to follow his lead.

In this scene, the script demanded that Pharaoh stand up to Corbin, as few Native Americans in the 1880s would have dared. Corbin presented a formidable figure even when wet. The rain glistened off his bald pate like some marble statue, his long bristles of gray beard as inviting as nails.

“Fine, I’ll take her,” Pharaoh yelled over the din and chaos. He grabbed Gardiner and forcibly lifted her into the harness with him.

“No, wait,” she screamed. “Austin, save me!” Her flowered hat flew off in the violent breeze.

But the old man was too late. With Gardiner wrapped around his side, Pharaoh plunged into the open air, above the ocean waves, as the life line tugged them along together. Kirkland’s camera crew had planned this pivotal moment for months.

The wide and telescopic lenses focused on the telling face of Manchester, the actress who expressed so many emotions as Gardiner within a matter of seconds. Fright, anger, surprise, and, ultimately, submission.

The cameras kept rolling as the rescuer and his reluctant passenger tussled in the air. Gardiner’s blonde hair, now wet and darkened, dangled off her back. A red scarf around her neck flew about wildly, symbolic of the mortal danger she felt. Eventually, the scarlet fabric covered Pharaoh’s face, enough so television viewers could only see his muscular physique, struggling with a rich white woman in his grasp.

Halfway across this gauntlet, an ocean breaker slammed into the couple. The forceful punch of seawater knocked out Gardiner, who suddenly stopped resisting. Her lifeless body fell backwards until halted by Pharaoh’s embrace. Their bodies remained entangled, suspended from the ropes in a nearly horizontal entwine, until they were slowly pulled to safety.

“Just like Winslow Homer,” Kirkland told his entourage as he watched the television monitors.

No one seemed to know what the famous director was talking about. No one knew the name of Winslow Homer, the artist whose painting of this dramatic scene graced my book. So Max looked at me directly.

“I love the way she clings to him. Reminds you of ‘Leda and the Swan,’ doesn’t it?” he continued, supremely satisfied. I nodded, without giving much heed to Kirkland’s telling allusion to a rape scene from Yeats.

Several cameras recorded the characters of Pharaoh and Gardiner as they disentangled from the ropes and pulley and collapsed on the beach. Pharaoh resuscitated Gardiner with a breath-of-life maneuver — a modern life-saving technique that probably wasn’t used in the 1880s but looked very much like a kiss on the screen.

Slowly, Gardiner’s eyes opened. From above, Kirkland’s drone cameras flew overhead with a steady buzz. They gave an almost Olympian perspective to the life-saving maneuvers on the beach. They recorded the dead bodies taken from the sea and lying on the sand, waiting to be claimed.

Kirkland’s flying cameras then came closer to the doomed ship, capturing the awkward escape of Corbin. Instead of relying on the life line ropes and pulley, Corbin lowered himself into a rowboat and arrived along the shoreline.

Stomping out of the rowboat, Corbin immediately confronted Pharaoh, who was resting on the shoreline with Gardiner.

“I should have you arrested,” Corbin hollered, his eyes filled with rage.

“What is your name?”

The Lifesaver wasn’t afraid to answer back.

“Stephen Pharaoh,” replied the actor Johnny Youngblood defiantly, in a heroic way his fans would surely enjoy.

There was no further struggle between the two men. Instead, the actress playing Corbin’s wife Margaret rushed up, crying with gratitude about his salvation. Mrs. Corbin feared the shipwreck, now beneath the waves, had submerged with her millionaire husband. Deliriously, she hugged and kissed Corbin and paid little mind to Gardiner’s presence in this mess.

Showing no fear, Pharaoh ignored Corbin and his ungrateful threats. As the cameras followed him, Pharaoh walked down the beach, along with the other tired rescuers. He headed toward the make-believe Hamptons life-saving station, recreated from old photos by Kirkland’s production crew.

Still winded from her rescue, Gardiner got up and brushed the wet sand from her dress. Instead of relying on her lover Corbin in this situation, she accepted the help of townspeople willing to bring her home to her own feckless husband, the town attorney. She looked round for Pharaoh but realized he had left without giving her the chance to thank him.

When the cameras finally stopped, all the actors heaved a sigh of relief and hastily exited the live-action set. Nearly everyone was drenched. Kirkland said there was no need for a second take. His stuntmen had done a magnificent job of reenactment, posing as nineteenth-century Lifesavers, without anyone drowning or getting hurt. On camera, this life-saving scene looked just like The Life Line painting to Max, its splendor successfully replicated on film.

“This is rapturous, simply rapturous!” Kirkland said ecstatically to those in the director’s circle. The tortuous planning and filming of this shipwreck scene — delayed for hours on this opening day — was finally accomplished without error.

Grabbing some blankets, Max hustled to the beachfront. He gave one blanket to his star actress Manchester, demanding another kiss from her.

With a sigh, Manchester obliged, merely as a sign of her contentment with how this opening scene turned out.

But Kirkland saved most of his affection for Vanessa Adams, the same red-headed young actress I had met at the coffee van hours earlier. Her turn-of-the-century clothes were barely damp because she had been part of the crowd scene on the beach.

Currently, Adams had no speaking role. Perhaps she hoped to change that omission as the project progressed. Max wrapped the last blanket around Vanessa’s shoulders and hugged her. I watched silently as they walked away from the beach together.

- Get link

- X

- Other Apps